Marriage is great for your finances—but avoid these three mistakes—Retirement Research Center

What problems could arise? Relationships can complicate your decision-making.

From an economist's perspective, one of the advantages of marriage is financial benefits. Marriage allows partners to share risks (e.g., one partner can work more if the other loses his or her job) and allows couples to take advantage of returns to scale (i.e., it is cheaper to maintain one household than two separate households). These benefits are why I am troubled by the approximately 30% decline in marriage rates over the past 40 years.

But marriage also complicates financial decisions. People who are not yet married may put off major decisions, such as saving for retirement. After getting married, couples need to realize that their retirement savings must ultimately be enough for two people, not just one. And, decisions around these savings must reflect both sets of personalities and preferences.

The truth is, couples—probably including you—make mistakes all the time. A study I conducted with colleagues Alicia Munnell and Wenliang Hou found that despite the financial benefits of marriage, married couples higher risk Retirement income is insufficient to maintain pre-retirement living standards. So, what went wrong? People can decide to tackle some issues in the new year, even before the couple gets married.

Error 1: Wait until you get married… to save

As marriage rates decline, people are getting married later. Since marriage is a milestone that often separates adolescence from adulthood, a logical question is how this delay affects retirement savings. Such delays could deprive people of years of contributions, employer matches and compounding interest.

To examine this question, a 2019 study I conducted linked marriage data to 401(k) savings and followed people before and after marriage. The study found that men were 13 percent more likely to participate in a 401(k) plan after marriage, and that when they did, their contributions were 6 percent higher. For women, the participation benefit from marriage is smaller (5%), but their contribution is larger, at 17%. Therefore, if the trend of delaying marriage continues, it may also lead to delays in saving.

The plan: Start saving now…regardless of your relationship status.

Mistake Two: Forgetting You May Be Saving for Two People

After getting married, couples would do well to remember one obvious point: You are now two people who are financially connected. Therefore, a couple with two incomes will need more retirement savings than a couple with one income because they need to replace more of their total income. But here's the thing: While retirement needs are a family issue, retirement savings are often a personal issue. Most people make savings decisions while working and without a spouse. Or, they might just follow the plan's default settings. If both people have retirement plans at work, these decisions may be fine. However, if one member of a couple has income but does not have a 401(k), their spouse will need to save more to replace that income. However, a study I conducted with Wenliang Hou shows that this is not the case. In terms of their income, families with two incomes but a 401(k) save about half as much as other couples (see Figure 1). In other words, savers don't realize they are saving money for two people.

Plans for dual-career couples: Make sure you know if the other member is saving, and if not, you can save more yourself.

Mistake Three: Exhibiting the Personality of a Low-Self-Controlled Spouse

Everyone who is getting married now knows that the key to getting married is the rest Marriage is simple: compromise. However, one study I found shows a flip side to this—sometimes, people with good financial habits will accommodate their less financially capable spouses.

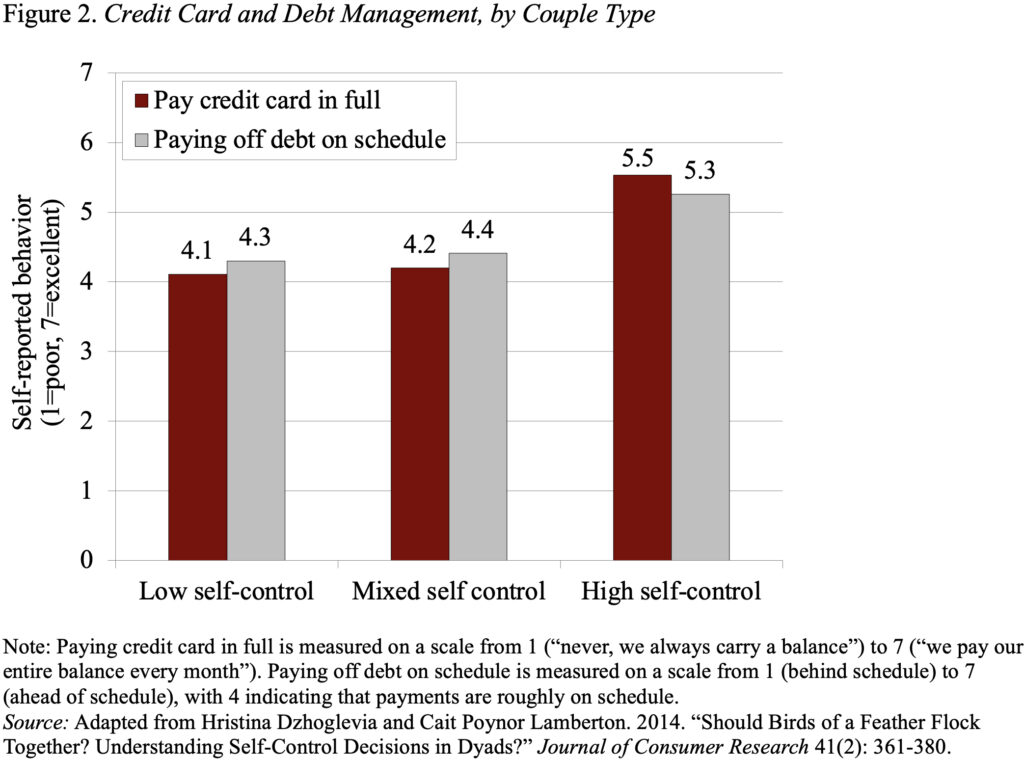

To measure competence, the study assessed couples' self-control. After all, research consistently shows that people with lower self-control save less, take on more debt, and make poorer financial choices. Couples were then identified as having two high-self-control members, two low-self-control members, or couples with mixed self-control.

Figure 2 shows one of the main results. When individuals were asked to report on a scale from 1 (poor) to 7 (excellent) how often they paid off their credit cards in full or paid off their debt on time, couples with high self-control looked much better than couples with low self-control. Not surprising. But, surprisingly, mixed-self-control couples looked just like low-self-control couples. It seems that in the process of trying to be a good spouse and adapt to their low-self-control spouse, the high-self-control spouse allows their finances to suffer.

Plans for high-self-control spouses vs. low-self-control partners: Try working with your spouse to make sure some of your good financial habits are reflected.

And here’s the lesson for everyone: Make sure you avoid these three common mistakes.