Does remote work expand the career of workers? – Retirement Research Center

this Underwear The main findings are:

- Previous research has shown that remote working can promote employment for elderly workers with disabilities, but how will it affect people without disabilities?

- The greater flexibility of remote working can lead to people working longer. Or, if the employer thinks this will reduce productivity, it may lead to an earlier exit.

- The study found that staff appear to be less likely to retire and even control job characteristics such as fields, industries and income.

- An open question is that this beneficial effect is due to remote work itself or to someone who wants a longer career to engage in remotely selected jobs.

introduce

For many, the transition from office to at least a certain amount of work at home five days a week seems to be the lasting impact of the pandemic. Recent research shows that the shift has helped people with late stages of disabilities, encouraging higher pre-pandemic employment rates.1 However, remote working may also affect older workers without disabilities. The flexibility and commuting provided by remote work can encourage later careers to work longer and delay retirement. Alternatively, employers can take a negative view of remote workers’ productivity, thus allowing the labor market to exit faster.

Given the importance of working longer than retirement safety, this Short Explore the possibilities that have been recently added to remote work Current population survey. The discussion organization is as follows. Part I provides context on remote work and its possible connection to retirement timing. The second part introduces the data and methods, and the third part introduces the results. The final part concludes that those who work remotely seem to be less likely to retire than those who don’t, and even control job characteristics such as fields, industries, and income.

background

Before the pandemic, remote work was not common. In 2019, only 6% to 8% of all working days were completed remotely. With the onset of the pandemic, that rate is more than tripled in early 2020. Despite a sharp decline by the end of 2021, the share of remote working in the days remains more than double the pre-pandemic rate.2

To date, most research on remote work and retirement has focused on workers with disabilities. These two observations stimulated this focus. First, during the pandemic, the employment-to-population ratio for people with disabilities has reached a year-on-year high.3 Second, workers with disabilities are larger during the pandemic than workers without disabilities.4 One study found that remote working increased employment rates for older workers with disabilities by 10% in the years following the pandemic — even controlling for tight post-pandemic labor markets and other factors.5

However, the question remains how remote work affects other workers approaching retirement. On the one hand, some studies have found that remote work can improve job satisfaction and reduce turnover, suggesting that this may encourage people to work longer.6 Remote work may also be part of a phased retirement plan that gives workers greater flexibility, but sacrifices salaries and responsibilities to make them willing to expand their careers.7

On the other hand, it is not clear how employers view remote work. While much of the evidence on the impact of remote work on productivity is positive, there is limited evidence that in some industries, this effect may be the opposite.8 And, anyway, employers have different views on remote work, and some have taken a negative view of it – especially in terms of innovation and creativity.9 To some extent, remote work actually reduces some workers’ productivity and even reduces people’s perceptions, and remote work may cause some older workers to be taken to retirement. Given the lack of clarity on the effectiveness of remote work, this Short Examine the impact of remote work on retirement hours for workers without disabilities.

Data and methods

This analysis is based on Current population survey (CPS) Basic monthly questionnaire used by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to estimate monthly unemployment rates. CPS added questions about remote work in October 2022 and has since included these new questions in the survey. Figure 1 shows the share of remote work at least weekly among employed people over the age of 55 without any physical, cognitive or sensory difficulties.10 From October 2022 to February 2025, this number hovers between 15% and 24%.

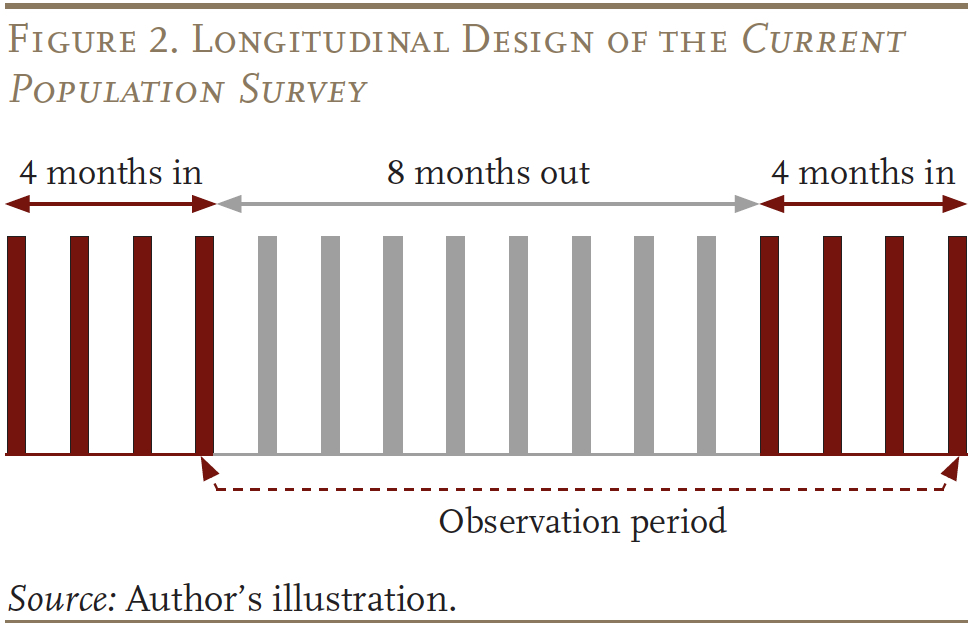

The problem is that these workers are at least more or less retired each week than other workers. To answer this question, the method relies on the panel nature of the monthly CPS. Specifically, respondents were surveyed for each of the four consecutive months. Then discharge from the sample for eight months; then re-enter the sample for four months.

The analysis explores how the labor status of these age groups over 55 years of age changes between the fourth month of the survey and the last month of the survey (see Figure 2). That is, is it someone who is still working in the fourth month of the last month or is it retired? The last group of workers considered in this analysis conducted a survey on their remote work in February 2024 and retired in February 2025. Throughout the period, 7.1% of those who worked remotely the following year retired in the second year, while not 9.0%.

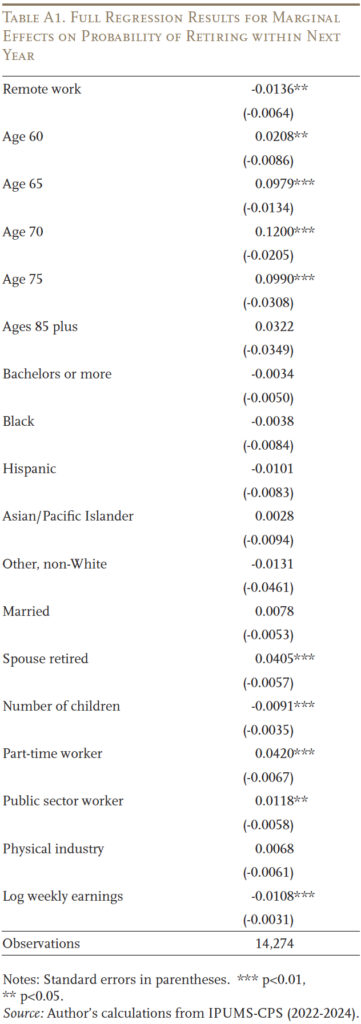

Therefore, at first glance, the distant work seems to be a little longer than the work, but there is a big difference between those who work and those who don’t follow several dimensions (see Table 1). In particular, remote workers are more likely to be educated in college, earn much more per week, and are less likely to work in the physics industry. To some extent, all of these characteristics are associated with longer occupations, so failure to control them will exaggerate the reduction in retirement associated with remote work. Of course, other characteristics that we cannot control may also work. For example, if older workers who always plan to extend their work life choose to work remotely is the easiest job, the impact of remote work on retirement will be exaggerated.

To illustrate these factors, regression analysis was performed to compare other similar people who happened to differ in remote working status. Regression analysis controls the above-mentioned population, family and work-related characteristics. The estimated regression is:

The probability of retirement = f (Remote work, age, education, race, family, work)

result

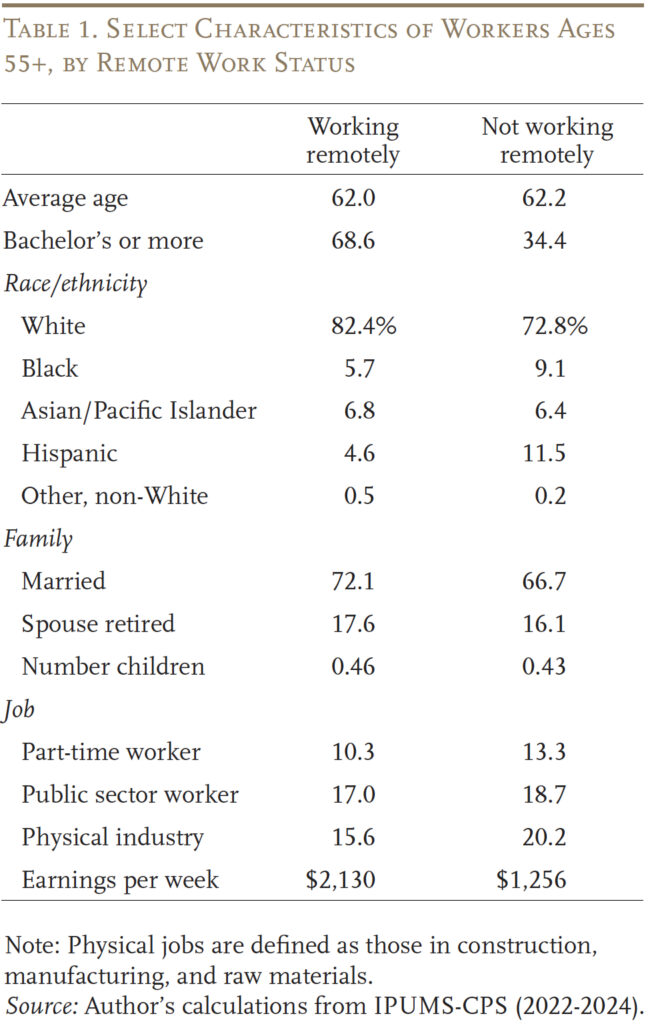

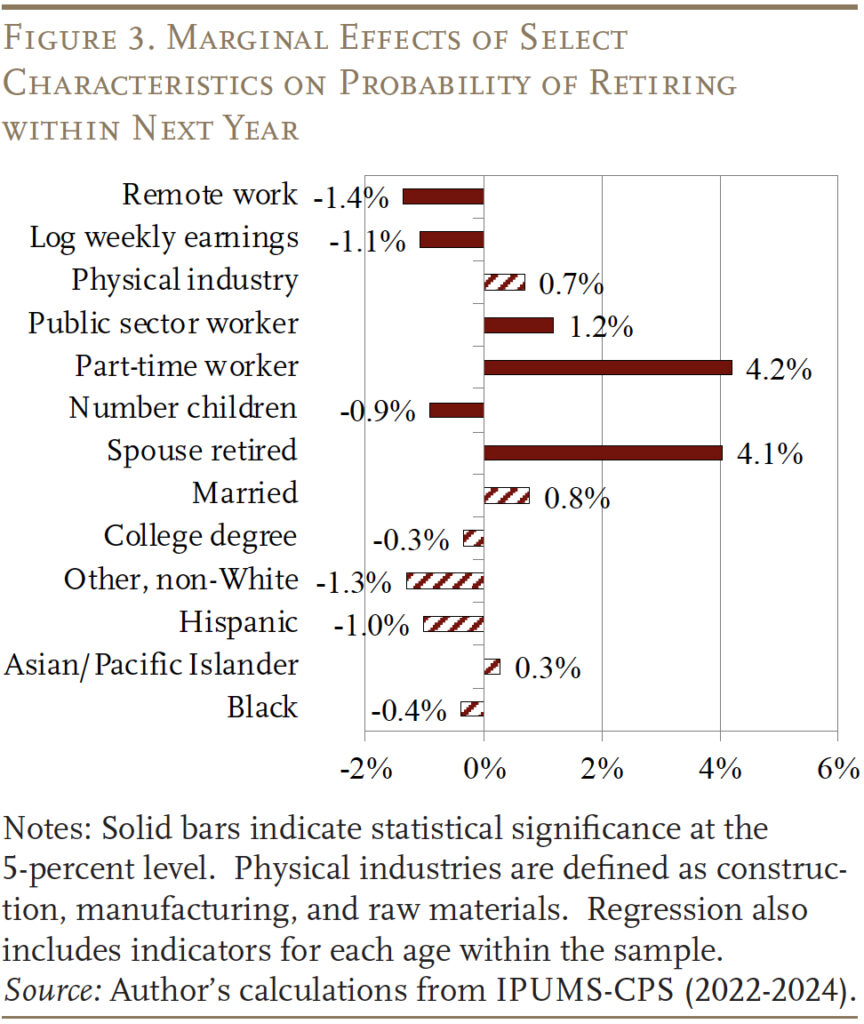

The regression results are shown in Figure 3.11 The main point is that remote work is associated with a statistically significant reduction in retirement probability even when controlling for population, family and work characteristics. People who work remotely are 1.4 percentage points less likely to retire than others like them. Given that 9.0% of this sample retires next year, it is a decrease of 14.4% (1.4/9.0).12 This reduction reflects two possibilities. First, the nature of remote work allows for longer occupations – causal effects. The second is workers who want longer workers to choose to work remotely, which makes it easier for them to expand their careers. Which of these two is driving the effect, which shows whether making it easier for other workers to work remotely will expand careers. Solving this problem is a useful area for future research.

Consistent with many previous studies, work characteristics appear to have statistically significant effects on retirement timing in addition to remote work. The results show that doubled income reduces the likelihood of retirement by 1.1 percentage points, i.e., jobs and part-time jobs in the public sector are associated with an increase in retirement probability, up by 1.2 and 4.2 percentage points, respectively. Family also seems to be important because the presence of dependent children reduces the likelihood of retirement, which may be due to financial constraints. Having a retired spouse has a predictable effect – 4.1 percentage points – more likely to retire. Race, race, and education are statistically trivial.

in conclusion

Remote work is still improving relative to pre-pandemic levels, and at least for some workers, it seems that they are still staying here. Given the savings of many Americans, it also takes longer. This good news Short That's what remote working seems to help with a longer career. Compared with other similar opponents, workers without disabilities are 1.4 percentage points less likely to retire within one year. Future research should focus on whether this result reflects aspects of remote work that improves occupational lifespan or the fact that those who wish to have a longer career choose to choose among such jobs. This question is important because it states whether providing remote work options to expand careers at the same time.

refer to

Barrero, Jose Maria, Nicholas Bloom and Steven J. Davis. 2023. “The evolution of working from home.” Economic Perspective Magazine 37 (4): 23-49.

Bloom, Nicholas, Ruobing Han and James Liang. 2024. “Hybrids working from home improve retention without compromising performance.” nature 630 (8018): 920-925.

Bloom, Nicholas, James Liang, John Roberts and Zhichun Jenny Ying. 2015. “Working from home? Evidence from China's experiment.” Economics Quarterly 130(1):165-218.

Carr, Dawn C., Christina Matz, Miles G. Taylor, and Ernest Gonzales. 2021. “The U.S. Retirement Transition: Models and Pathways to Full-Time Work.” Public Policy and Aging Report 31 (3): 71-77.

Choudhury, Prithwiraj, Tarun Khanna, Christos A. Makridis and Kyle Schirmann. 2024. “Is the work of hybrid power the best of both worlds? Evidence from field experiments.” Economic and Statistical Reviews: 1-24.

Emmanuel, Natalia and Emma Harrington. 2024. “Remote Work? Selection, Therapy and Remote Work Market.” American Journal of Economics: Applied Economics 16(4):528-559.

American ipums. 2025. IPUMSCPS: Version 12.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota.

Kessler Foundation. 2022. “June 2022 Job Report: Employment for people with disabilities reaches an all-time high.” National trends in national disability employment reports. East Hannover, New Jersey.

Liu, Siyan and Laura D. Quinby. 2024. “Did remote work improve employment outcomes for disabled elderly people?” Working document 2024-12. Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts: Boston College Retirement Research Center.

Max, Cassandra and Hannah Rubington. 2024. “The impact of family work on labor on workers with disabilities.” On the Economics Blog. St. Louis, Missouri: St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank.

Pabilonia, Sabrina W. and Jill J. Redmond. 2024. “Remote work since the pandemic and its impact on productivity.” Exceeded the number 13 (8). Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Tahlyan, Divyakant, Hani Mahmassani, Amanda Stathopoulos, Maher, Susan Shaheen, Joan Walker and Breton Johnson. 2024. “Face-to-face, hybrid or remote? Employers’ perceptions of the future after the pandemic.” Transportation Research Section A: Policy and Practice 190:104273.

U.S. Census Bureau. Current population survey, 2022-2025. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

appendix