Can we help people improve their life expectancy? – Center for Retirement Research

this underwear The main findings are:

- Knowing how long we live can influence our retirement decisions, but many people underestimate their chances of living into old age.

- This study tested whether providing simple information could help improve people's estimates of their age in old age.

- The intervention was highly effective for about a quarter of the participants, particularly those who relied on experts to guide their thinking.

- But this intervention was ineffective for many participants who relied on parental experience, so more research is needed to help them.

introduce

Knowing how long we live can influence important decisions, such as how much to save or whether to buy an annuity. However, many people underestimate their chances of living into old age, which may lead them to save too little and avoid annuities, potentially reducing their financial security in retirement.

this short As part of upcoming research, we will explore longevity awareness in more depth.1 It examined whether a simple and low-cost information intervention could increase longevity awareness – people's knowledge of how long they are likely to live. To this end, the study conducted an experiment with a control group and two treatment groups. The treatment groups all received educational materials designed to increase their awareness of how long they were likely to live.

this short Its structure is as follows. Part One provides background on longevity awareness. Section 2 describes the investigation and experiments. Section 3 presents the results and shows that the intervention was reasonably effective, but only for approximately a quarter of the participants. The final section concludes that low-cost interventions can work for specific populations and that the less information the better. One question for future research is how to reach those who do not receive such interventions.

background

Previous research has shown that adults aged 55-70 tend to be pessimistic about their lifespan because their guesses about their chances of living older (dashed line in Figure 1) are lower than objective data (solid line).2 This pessimism can negatively impact savings and annuitization decisions because individuals must decide whether to purchase an annuity and how to withdraw their 401(k) balances at an age when life expectancy is most likely to be underestimated.

The question is whether educational interventions can help people become more realistic about their chances of living into old age. Previous research has found that providing people with data on their chances of living to a very old age increases their awareness of longevity, whereas simply providing data on life expectancy does not.3 This finding suggests that people may be aware of average life expectancy, rather than the likelihood that they will live to old age. In addition, many people's life expectancy is determined by the age at which their parents died or by media reports, neither of which take into account possible future improvements in life expectancy.4

Surveys and Randomized Controlled Trials

Based on these two empirical facts about the potential effectiveness of interventions and the traditional sources people rely on, our experiment tested two different informational interventions to address the different biases individuals may have about longevity. The first is “tail risk,” which is not knowing the probability of living to a very old age. Respondents in the first treatment group were provided with some data on tail risk from the Social Security Administration. The second bias is not understanding the extent to which longevity has generally improved over time. Respondents assigned to the second intervention group received the same data as the first treatment group, plus additional content about people living longer than their parents. See box for details on survey sample.

Box. survey sample

The experiment was part of a larger survey on longevity awareness and annuity literacy, designed in partnership with Pacific Life and run by Greenwald Research Associates. The survey was conducted in the first quarter of 2025 with 2,204 respondents. Participants were aged 21-70, with 1,950 aged 45-70. All respondents were employed full-time and had 401(k)-type retirement savings plans. The information intervention experiment only included participants aged 45-70 years.

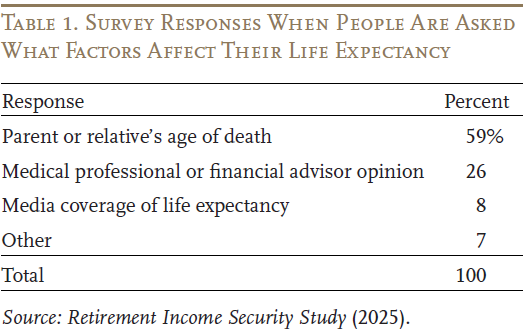

Participants were first asked to select the most important factor they used to estimate life expectancy. As in previous studies, our survey found that most respondents base their assessment on the age at death of a parent (or other relative), while approximately 10% base their assessment on media reports (see Table 1). Interestingly, about a quarter of respondents said they relied on the advice of health or financial professionals.

Next, to determine whether a simple information intervention could help correct lifespan misconceptions, we divided survey participants into three groups: a control group and two intervention groups.

The control group was given unrelated material that did not relate to improvements in life expectancy, probability of survival, or mortality over time.5 After the control group participants read this, they were asked to estimate how long they were likely to live and the probability of living to be 75, 80, 85… and 100 years old.

The first treatment group obtained information from Social Security death records about their probabilities of living to age 90 and 100. Like the control group, they were then asked to estimate how long they thought they would live and the probability of living to various ages between 75 and 100. As mentioned above, this approach builds on previous findings that educating individuals about the probability of living to older ages can improve not only life expectancy data but also longevity awareness. When considering whether to purchase guaranteed lifetime income, it is particularly important to identify effective ways to improve understanding of tail probabilities, as tail risk is underwritten by the product.6

However, as noted, most people's life expectancy depends on the age at which their parents died. Interventions that tell how long people are likely to live relative to their parents (or grandparents for a young person) have not been studied before. So, in addition to data on the likelihood of living to an older age, the second treatment group also obtained information about lifespan extension in the cohort and how much longer people lived compared to their parents or grandparents. Then, like the other groups, they were asked to estimate their probabilities of living to various ages, between 75 and 100.

result

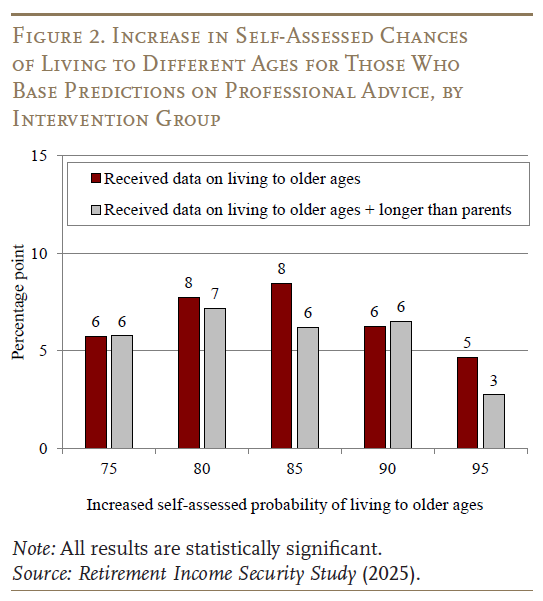

These interventions worked well, but only among one group of respondents—those who predicted life expectancy based on the advice of a medical professional or financial advisor. Respondents who trusted experts became more optimistic about living into old age after receiving both information interventions. This group represents a little more than a quarter of survey respondents receiving treatment. In contrast, the intervention had no effect on those whose life expectancy was assessed based on age at parental death or other factors. Figure 2 summarizes the results for those who predicted life expectancy based on professional advice. For example, among these people, those in the first treatment group (who only received information about living to an older age) were 8 percentage points more likely than those in the control group to say they would live to at least age 85. Interestingly, simply providing data on the likelihood of living to an older age was as effective, if not more effective, than having the second treatment group receive additional data on living longer than their parents.7

How do the interventions compare to financial advisors?

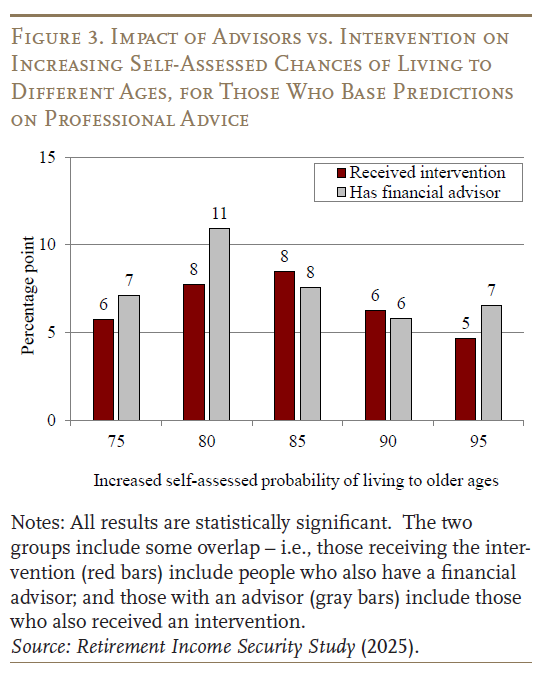

An interesting question is how does the impact of the intervention compare to the effect of having a financial advisor (again, for the quarter of respondents who rely on professional advice)? Not surprisingly, people who work with a financial advisor are more optimistic about longevity than those without an advisor (see Figure 3).8

More interestingly, however, if we compare the impact of the intervention with the impact of the consultant, we see that the intervention has a similar impact on people's predictions of lifespan into old age. Although these interventions only work for about a quarter of people (those who trust professionals), the results are still encouraging because not everyone has access to a financial advisor. In short, these information interventions can be a cost-effective way to increase longevity awareness.9

Can interventions help improve financial and annuity literacy?

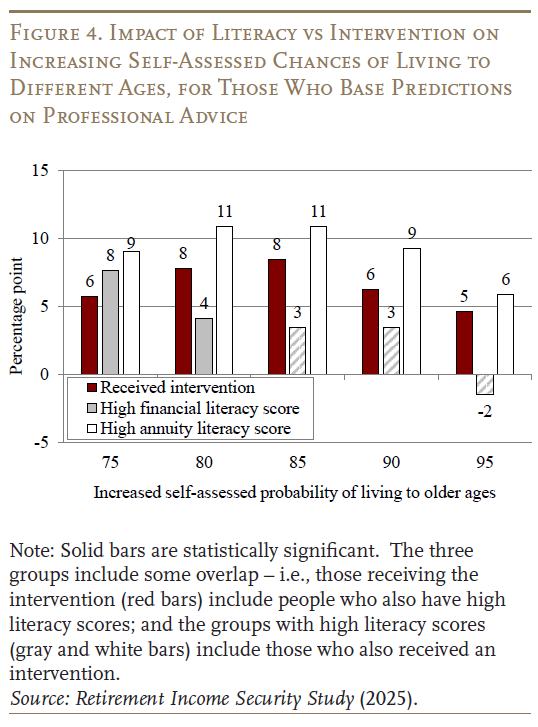

Next, we compared these interventions with those with higher financial or annuity literacy. Not surprisingly, people with higher financial or annuity literacy are more optimistic about longevity than those with lower literacy (see Figure 4).

Interestingly, Figure 4 shows that the intervention was more consistent in improving longevity optimism relative to higher levels of financial literacy, although the effect was smaller than for those with higher levels of annuity literacy.10 Since developing financial and annuity literacy can take years, the impact of the information intervention is encouraging.

in conclusion

Knowing how long we live can influence key decisions, such as how much to save or whether to buy an annuity. However, many people underestimate their likelihood of living into old age. We tested whether a brief informational intervention could help correct people's misconceptions. The experimental results provide two important lessons. First, only a small group of people are willing to accept the intervention—intuitively, those who trust professionals to provide information. For this group, the intervention was effective. For other groups, more research is needed to determine how to increase longevity awareness, as these individuals tend not to base their assessments on expert opinion, resulting in less effective intervention by experimenters.

The second lesson is that providing simple materials is just as effective, if not better, than providing more detailed interventions. Although neither intervention was particularly long-term, our results suggest that simply providing some data on the likelihood of surviving to a certain age is enough to improve respondents' perceptions of surviving into old age, and that providing more data on mortality reductions over time does not improve outcomes.

refer to

Arapakis, Carolos, Angel Chen, Qi Sun, and Gal Wetterstein. (coming soon). Retirement Income Security Research. Newport Beach, CA: Pacific Living.

Arapakis, Carolos, and Gayle Wettstein. 2023. “Longevity Risk: An Article.” Special Report. Chestnut Hill, MA: Boston College Center for Retirement Research.

Hurwitz, Abigail, Olivia S. Mitchell, and Olly Sade. 2022. “Testing Methods to Enhance Longevity Awareness.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 204:466-475.

Hurwitz, Abigail, and Olivia Mitchell. 2022. “Financial Regret and Longevity Awareness in Old Age.” Working Paper No. 2022-25. Philadelphia, PA: Wharton Pension Research Committee, University of Pennsylvania.