Election of Mexico's first Supreme Court Justices aroused hope and skepticism within 170 years

Mexico City (AP) – During the Mexico Supreme Court campaign, Hugo Aguilar has sent a simple message: he will be the one who will eventually speak out to the Mexicans as one of the highest governments.

“It’s our turn as indigenous people … to make a decision in this country,” he said before Sunday’s first judicial election in Mexican history.

According to Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, now 52-year-old Aguilar is a lawyer for the people of Mixtec in the southern state of Oaxaca and will become the Supreme Court justice of the Latin American country for nearly 170 years. He can lead the High Court. The last indigenous justice was the Mexican hero and former president, Benito Juárez, who ran in court from 1857 to 1858.

For some, Aguilar has become a symbol of the forgotten edge of 23 million indigenous peoples in Mexican society. But others strongly criticized his past and feared that he would not replace them, but stood with the ruling party Morena and brought him to court.

Win the highest voting championship in controversial competition

Supporters cite Aguilar’s long history with indigenous rights, while critics say he has recently helped push the party’s agenda to manage the party, including a large-scale infrastructure project by former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador at the expense of indigenous communities. Aguilar's team said he would not comment until the official results were confirmed.

“He is not an indigenous candidate,” said Francisco López Bárcenas, a Mixtec lawyer in the same area where Aguilar once worked with. He praised the election of Indigenous Justice, but said: “He is an Indigenous person who became a candidate.”

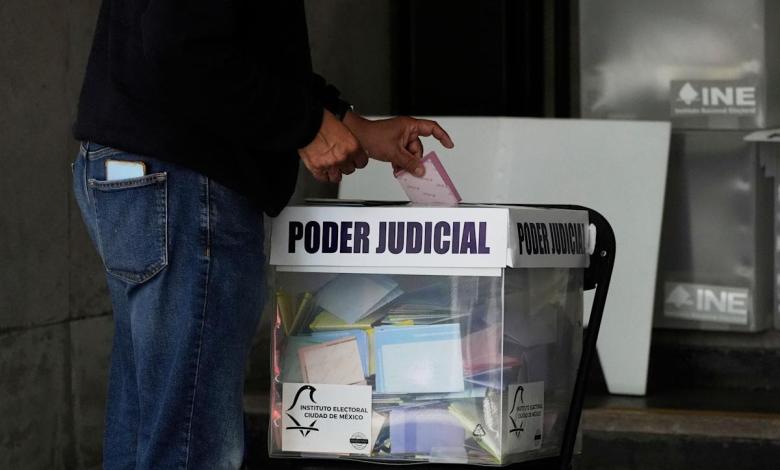

Aguilar was elected in Mexico's first judicial election, a process criticized for weakening Mexico's checks and balances.

López Obrador and his party overhauled the judicial system, and populist leaders continued to be well with it. Instead of appointing judges through experience, voters elected judges to 2,600 federal, state and local positions. But voting marks a low voter turnout, at about 13%.

López Obrador and his successor and Protege President Claudia Sheinbaum claimed that the election would cut corruption in the courts. The judges, watchdogs and political opposition said it was a blatant attempt to use the party's political visibility to pile up the courts and control all three branches of the Mexican government.

Although votes are still counted in many races, the statistics on the scores of nine Supreme Court justices are the first. The vast majority of judges maintain strong ties with the ruling party, giving Morena potential control over the High Court. Aguilar's name is one of the people who appear in the pamphlet, suggesting which election authorities are investigating which candidates.

Focus on indigenous rights

Aguilar voted more than 6 million more than any other candidate, including three currently serving in the Supreme Court. Victory opened up the possibility of Aguilar not only serving on the court, but leading it.

Critics attributed his victory to Mexico’s popular president, repeatedly saying she wants the Indigenous Justice of the Supreme Court to be ahead of the election. On Wednesday, she said she was glad he was on the court.

“He is a very good lawyer,” she said. “I have the honor of not only knowing that his work is on indigenous issues, but overall. He has a broad knowledge and is a modest and simple person.”

The Supreme Court has issued a decision that, for example, an interpreter who explains his native language and defense attorney can assist the rights of the indigenous peoples in any legal process. However, in the case of large projects, there are still major issues, such as territorial disputes.

Aguilar began his career in the capital of Oaxaca, a group that works in Sermixe, which advocates law students in their 20s.

Sofía Robles, a member of the organization, remembers the passion of young Aguilar, choosing to become a lawyer, advocating for the frequent living of indigenous communities that are impoverished and illegal.

“He has this belief and there are a lot of things he doesn't fit in,” said Robles, 63. “From the beginning, he knew where he came from.”

Despite coming from a modest working-class family, he will work for the organization for free after the law class. Later, he worked there as a lawyer for agricultural issues for 13 years. After the Zapatista Uprising in 1994, after the guerrilla movement to fight for indigenous rights in southern Mexico, Aguilar worked to carry out constitutional reforms to recognize the fundamental rights of indigenous peoples in Mexico.

Robles said she thought he would bring the battle she saw in him to the Supreme Court.

“He gave us hope,” she said. “Aguilar will be an example of future generations.”

Contact a political party

But others like Romelgonzález Díaz, who are members of the Xpujil Indigenous Parliament of the Mayan community in southern Mexico, are doubtful about whether Aguilar really acts as a voice for its community.

Aguilar's work came under fire when he joined the government's National Indigenous Peoples Institute when the government began in 2018. At that time, he began working on the large Maya trains that were strongly criticized by environmentalists, indigenous communities and even the United Nations.

The train ran around a rough cycle on the Yucatan Peninsula and had cut down large areas of jungle and irreversibly damaged an ancient cave system, sacred by the indigenous population there. Aguilar's mission is to investigate the potential impact of trains, listen to the attention of local indigenous communities, and inform them of the consequences.

At that time, González Díaz met Aguilar, who arrived with a handful of government officials who sat with him in the small community of Xpujil for hours and provided sparse details about the negative parts of the project.

González Díaz's organization is one of many organizations that have taken legal action against the government, trying to stop the construction of trains in order to fail to properly study the impact of the project.

The project wasted the remaining environmental damage that left him distrusts Aguilar.

“The concern for Hugo is: Who do he mean?” González Díaz said. “Would he represent the (Morena) party or the indigenous people?”