How much has social security claimed to have increased? – Retirement Research Center

this Underwear The main findings are:

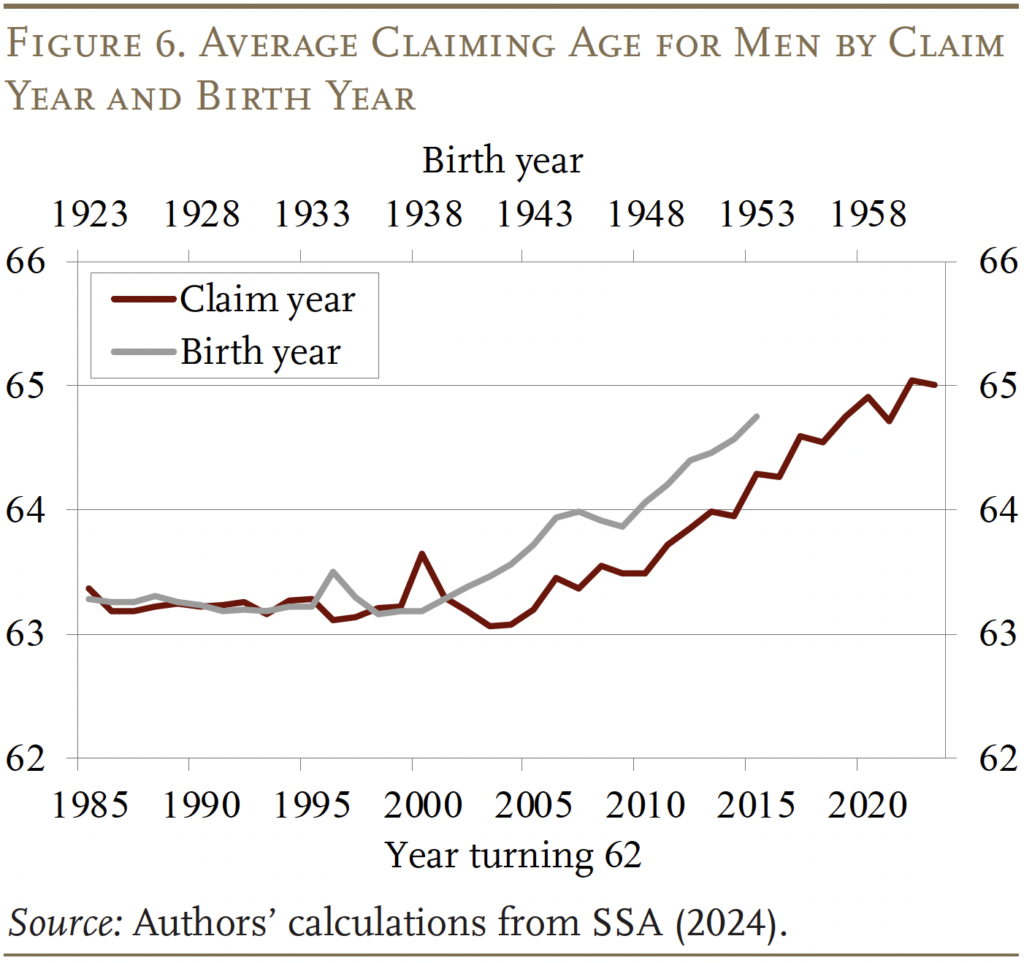

- The average retirement age has increased by three years since the mid-1990s.

- The question is, to what extent does the work translate into delaying claims for Social Security benefits?

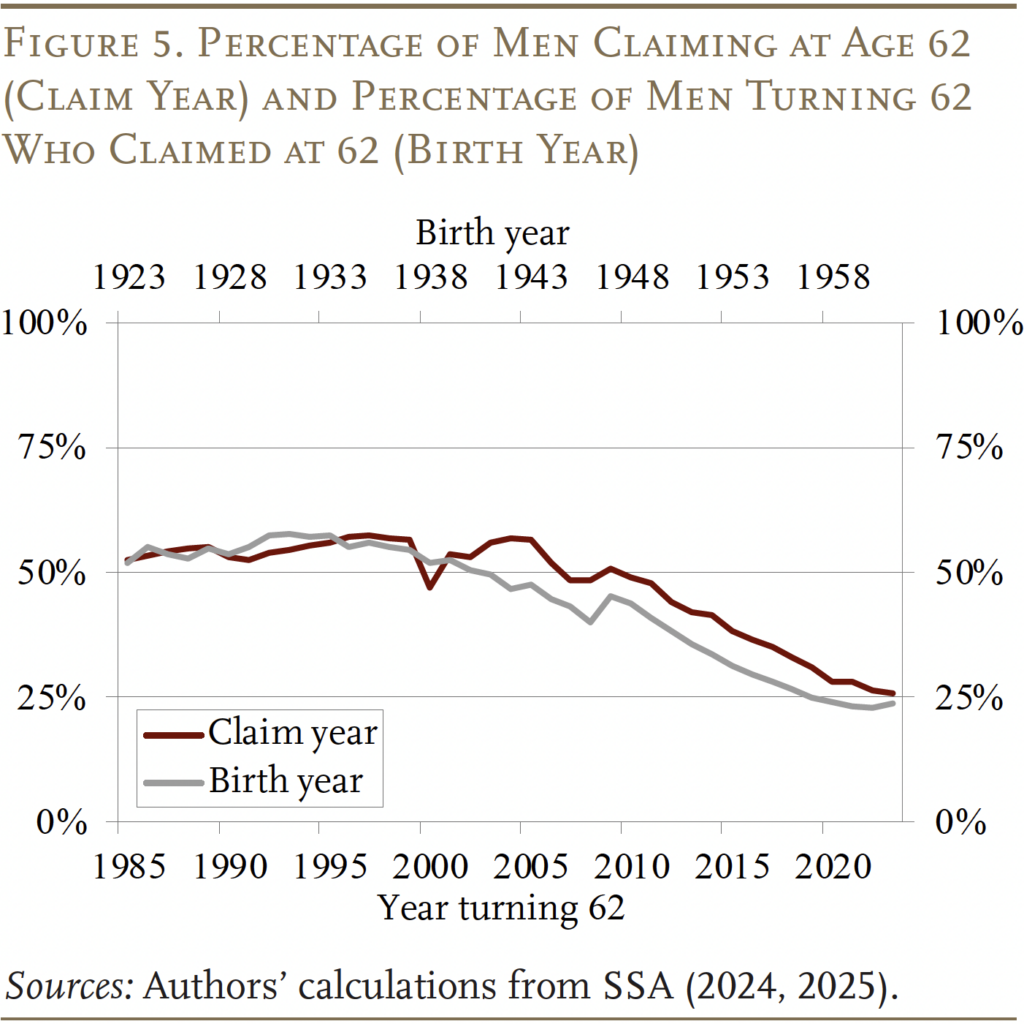

- There are two indicators here: 1) share of all initial claimants at all ages 62; 2) share of all workers Age 62 years old Claim 62.

- Both have shown a huge decline in share of 62 people over the past two decades, and this trend has even continued through Covid.

- As a result, the average claim age increased by about two years during this period, slightly below the average retirement age.

introduce

When possible, working longer hours have been generally accepted as good advice for safe retirement. It directly increases current income; it allows people to contribute more to 401(k)s; it shortens retirement periods; and, importantly, delaying claims for Social Security leads to higher monthly gains. The good news is people responded. The long-term trend of early retirement ceased in the mid-1980s, and the age of labor force participation began to increase in the mid-1990s, and since then, the average retirement age has increased by three years. The question is how much longer it translates into delayed claims for Social Security benefits.

Some information can be collected from claims data released annually by the U.S. Social Security Agency (SSA). These data are shown for All workers who request benefits within a given year, The percentage of age between 62, 63, 64 years old is beneficial for any given year. However, when the size of the group 62 increases significantly each year, the claim data underestimates the trend of future claims. That is, the data will show that 62-year-old claimants make up a larger proportion of new claimants in a given year, even if they immediately make up a smaller percentage of the age group of 62 years. To accurately follow claims over time, the queue data must be viewed. Such data shows that Among potential claimants who may be over 62 years of age in a particular year Ask for percentage as soon as possible. this Short Use two data sources to view the long-term trends of short-term before and after-claims.

The discussion goes on as follows. The first section uses annual claims data to record changes in claims from 2019 to 2023, and 62 claims percentages from 1985 to 2023. The second section describes the number of people who are over 62 years of age each year since the mid-1990s and discusses how this “peer effect” exaggerates the number required to be 62 in published numbers. It also noted that recently, 62-year-olds have been stable as part of the population, so the amount of changes in age groups does not distort the current comparison. However, birth year data is essential for any historical comparison, so the third part compares from 1985 to 2023, with the claim age and the claim age for the birth year being 62 years, using the average claim age for the two data sources. The final section concluded that people are delaying claims regardless of the data source, although the two-year age of the average claim age increased from 63 to 65, slightly lower than the three-year increase in the average retirement age.

Data for the year of claim

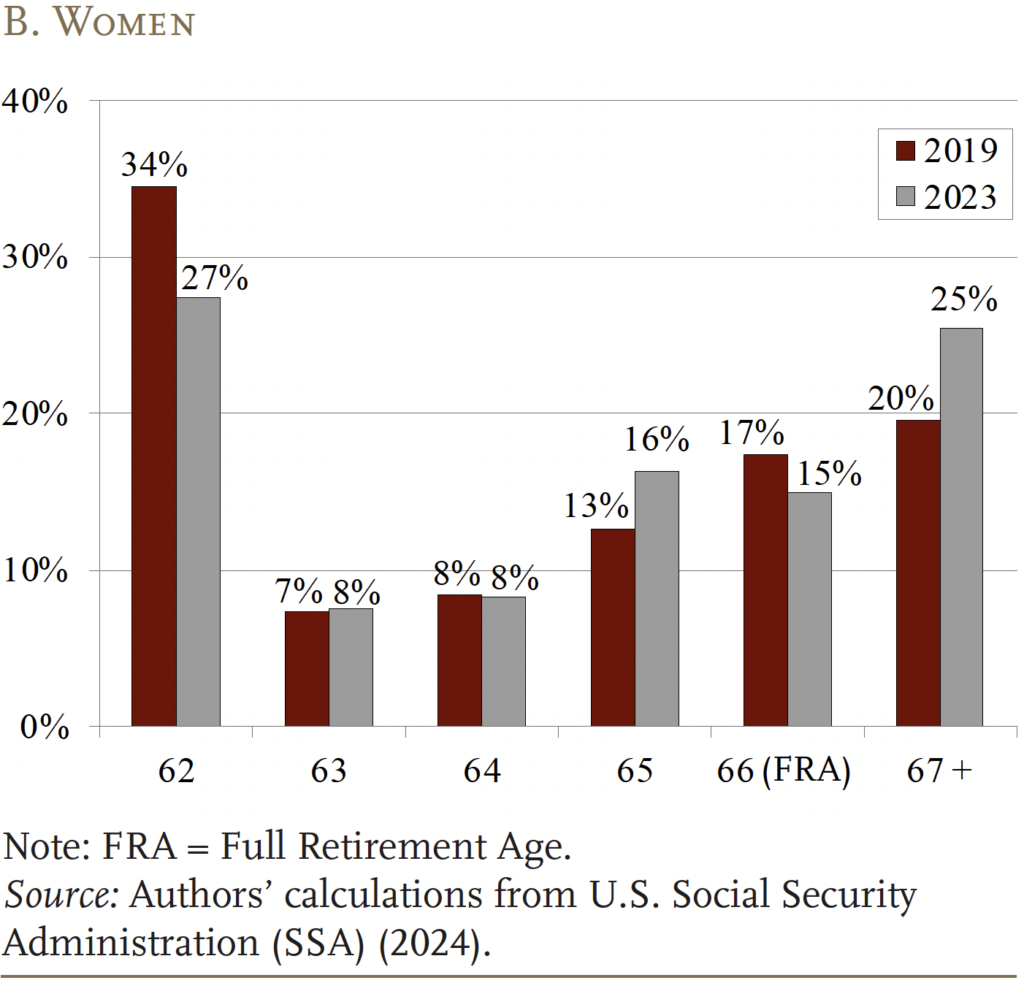

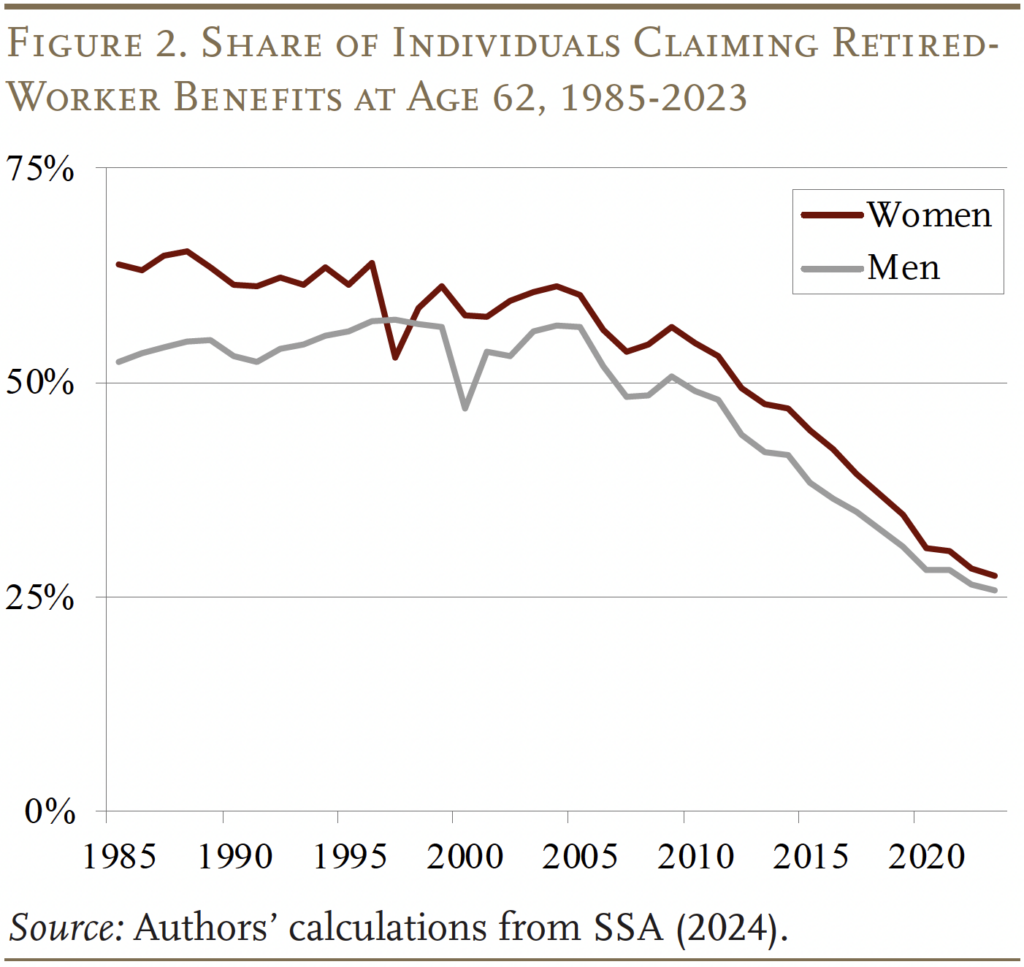

Many articles have been written about the impact of Covid on the working model of the elderly. The consensus is that while the pandemic has left many older people unemployed, it has not led to earlier self-reported retirement or social security requirements.1 Indeed, men and women supported early assessments through allocation of claims of age. Among those who claimed benefits in 2019 and 2023, men and women accounted for smaller share of men and women aged 62, and a larger share of claims over 67 years (see Figures 1A and 1B).

These same data can be used to create a history of early claims during the period 1985-2023 (see Figure 2). During that time, despite rapid increase in bias among 62-year-olds, the claim earlier percentage began to decline in 2005 – from about 60% to 30%.

The problem with this number is that this pattern is inconsistent with the fact that the rise in work actually began in the mid-1990s, not in 2005. The inconsistency is that the number of people who turn to 62 years old began to increase significantly in 1997, which makes the claims year data look like many people claiming early – choosing the so-called “colleague” and “population” effect.2

“Quote” effect

One example provides the intuition behind the “queue” effect. It is assumed that the beneficiary can only claim compensation at age 62 or 63, and 55% of all persons born in any given year will claim at age 62, while the other 45% will be 63 years of age the second year. If the number of people over 63 is 62 is 62, then the number of people stays unchanged from one year to the next year, then the SSA will publish the data on the SSA, and then the SSA will publish the data on the SSA and tell the same data at the same time. Conversely, if the number of people reaching 62 years old increases by 10% over the year, the data released by the SSA will show that 57% of those who enjoy benefits each year are 62 years old, while 43% are 63 years old.3 In this case, the SSA published data will exceed the 62-year-old constant claim rate for each cohort.

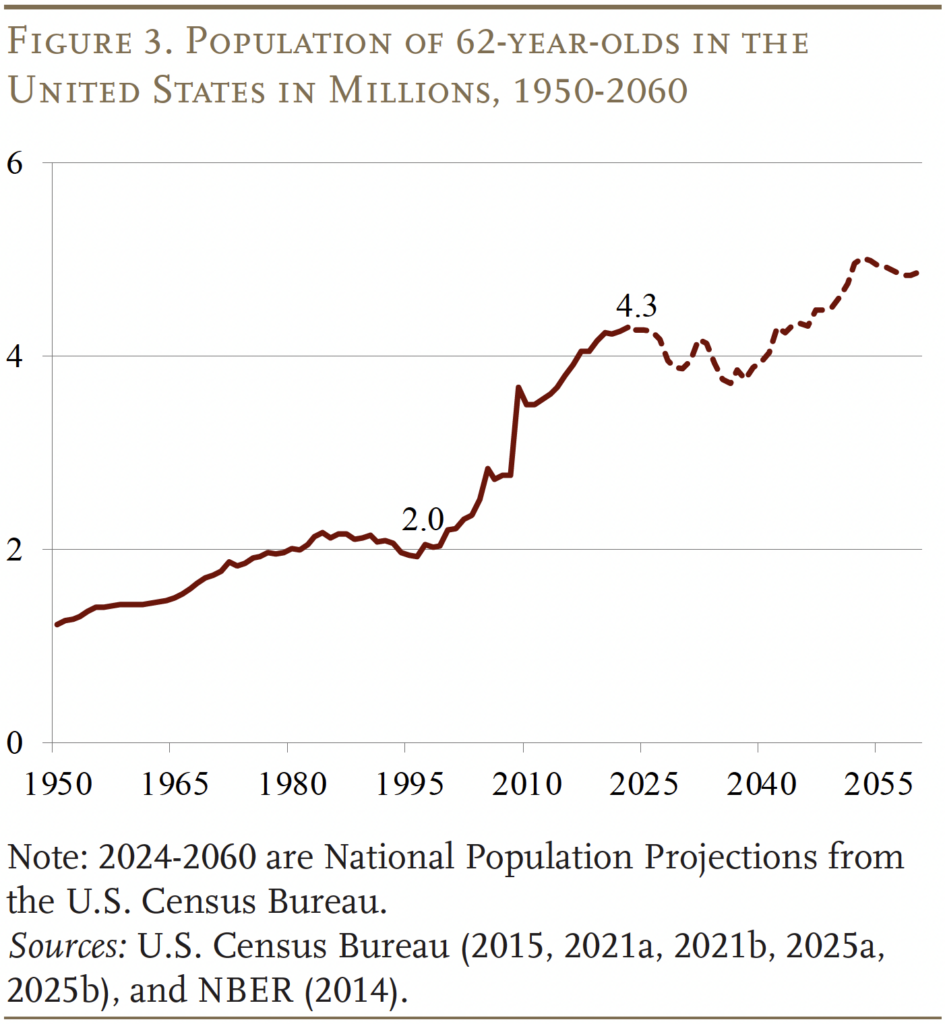

In fact, the number of individuals over the age of 62 began to increase significantly around 1997. Between 1997 and 2023, the annual traffic increased from 20 million to 4.3 million (see Figure 3). This increase greatly changes the age structure of the population eligible for retirement benefits.

The only way to isolate a 62-year-old behavior is to determine the percentage of all born people in a given year, who claim retired workers’ benefits are 62. This is possible because SSA has no data on the number of people eligible for retired workers' benefits in the year of birth. The task then is to divide the total between claims ages based on data published by the SSA.4

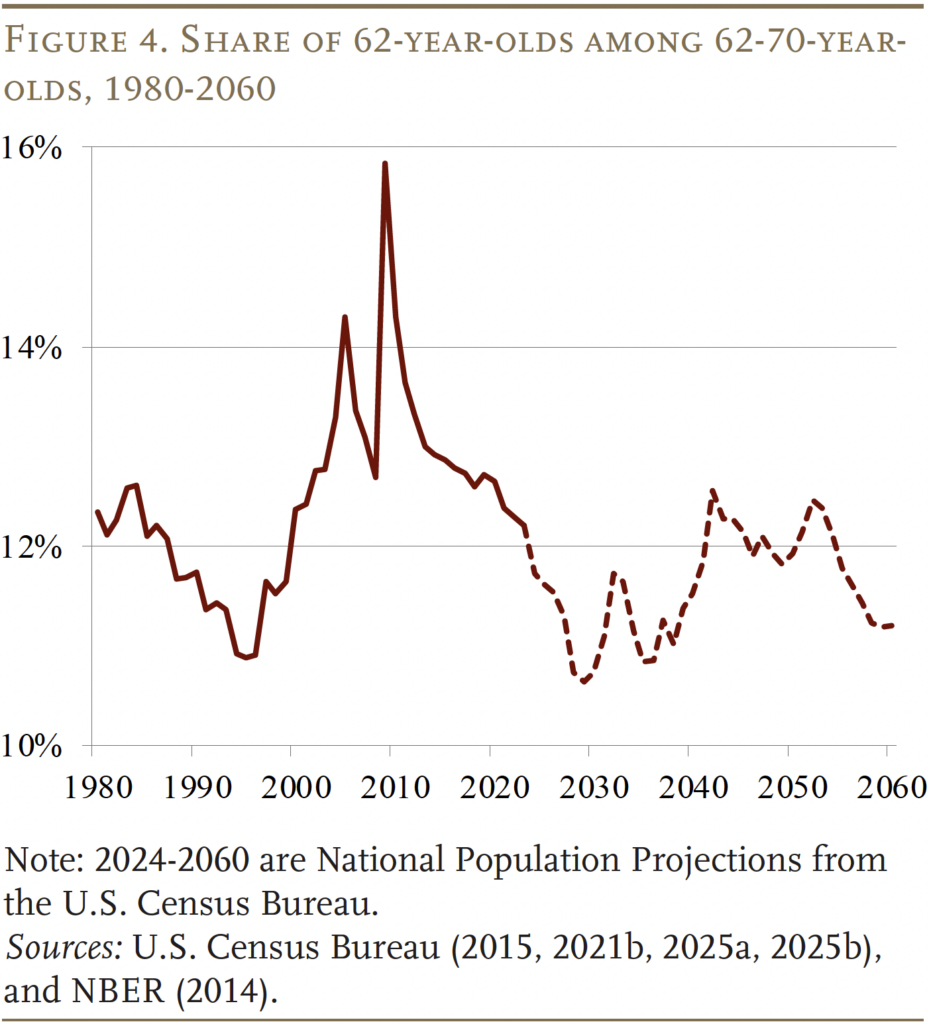

Before reporting results, it should be noted that the “cohort effect” is only related to evaluating long-term trends. The share of 62-year-olds in the 62-70 has now recovered to about 12% of the total (see Figure 4), meaning that currently, data published by claim age by claim age will provide a meaningful description of claims trends. That is, there is no cohort effect for published data between 2019 and 2023. However, for historical perspectives, birth year data remains crucial.

Comparison of the results of the year of claim and the year of birth

Figure 5 compares the percentage of men who have claimed in the year of claim and the year of birth (same category) of 62 years old. Both methods provided very similar results before 1997. After that, the two series began to diverge. The cohort data reflects the rise in labor activity starting from the mid-1990s – longer lifespans and extended later requirements – and over the past three decades, labor activity has shown a greater decline in lifespan than the claims age data.

Figure 6 shows the trends in the average age of men from the year of claim and birth year from 1985 to 2023 (62 people after 2015 to less than 70 years of age in 2023). As one would expect, the increase in using birth year data is greater, but both support the argument that retirement delays are accompanied by delays in claims. However, the delay in claims (even using birth year data) is only about two years, slightly lower than the three-year increase in average retirement age.5

in conclusion

The good news is that before Covid, trends over the past 20 years have shown that once qualifying, the percentage of earnings at 62-year-olds claiming sharply declines, and that trend continues through Covid. As a result, although both the birth year data and the claim age data indicate an increase in the average claim age, an increase in the average retirement age of three years was increased.

refer to

Munnell, Alicia H. 2025. “Will the average retirement age continue to rise?” in short 25-8. Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts: Boston College Retirement Research Center.

National Bureau of Economic Research. 2014. “Inter-census population estimates in the United States.” Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Quinby, Laura D., Matthew S. Rutledge, and Gal Wettstein. 2021. “How does Covid-19 affect labor force participation in older workers?” Working Paper 2021-13. Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts: Boston College Retirement Research Center.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2025a. “National Demographic Characteristics: 2010-2019.” Washington, DC.

___________. 2025b. “National Demographic Characteristics: 2020-2024.” Washington, DC.

___________. 2021a. “National Cross Table: 1900-1990.” Washington, DC.

___________. 2021b. “Countries Cross Table: 2000-2010.” Washington, DC.

___________. 2015. “National Population Forecast: Age, Gender, Race and Ethnic Division of the United States in 2014-2060” on the CDC Wonder Online Database. Washington, DC.

US Social Security Agency. 2025. Unpublished data on initial social security benefits awards and eligibility status. Baltimore, Maryland

___________. 2024. Annual Statistical Supplement, 2024. SSA Publication No. 13-11700. Baltimore, Maryland