People work longer, but will they ask for social security in the future? – Retirement Research Center

Two different measures tell a similar story.

Working longer has been widely accepted as a good advice for safe retirement. It directly increases current income; it allows people to contribute more to 401(k)s; it shortens retirement periods; and, importantly, delaying claims for Social Security leads to higher monthly gains. The good news is people responded. The long-term trend of early retirement ceased in the mid-1980s, and the age of labor force participation began to increase in the mid-1990s, and since then, the average retirement age has increased by three years. The question is how much longer it translates into delayed claims for Social Security benefits.

Some information can be collected from claims data released annually by the U.S. Social Security Agency (SSA). These data are shown for All workers who request benefits within a given year, The percentage of age between 62, 63, 64 years old is beneficial for any given year. However, when the size of the group 62 increases significantly each year, the claim data underestimates the trend of future claims. That is, the data will show that 62-year-old claimants make up a larger proportion of new claimants in a given year, even if they immediately make up a smaller percentage of the age group of 62 years. To accurately follow claims over time, the queue data must be viewed. Such data shows that Among potential claimants who may be over 62 years of age in a particular year Ask for percentage as soon as possible. In a recent study, we used two data sources to study long-term trends in claims.

Find out if people require later and work longer to see the percentage of workers who receive benefits at the age of 62. Figure 1 shows the percentage of men claiming at age 62 according to the two methods mentioned above. The claim year shows the percentage of all claims in a given year at age 62; the birth year shows the percentage of people born in a given year at age 62. Both methods provided very similar results before 1997. After that, the two series began to diverge. The birth year data reflects the rise in labor activity starting from the mid-1990s, which has declined significantly over the past three decades than the decline in claims age data.

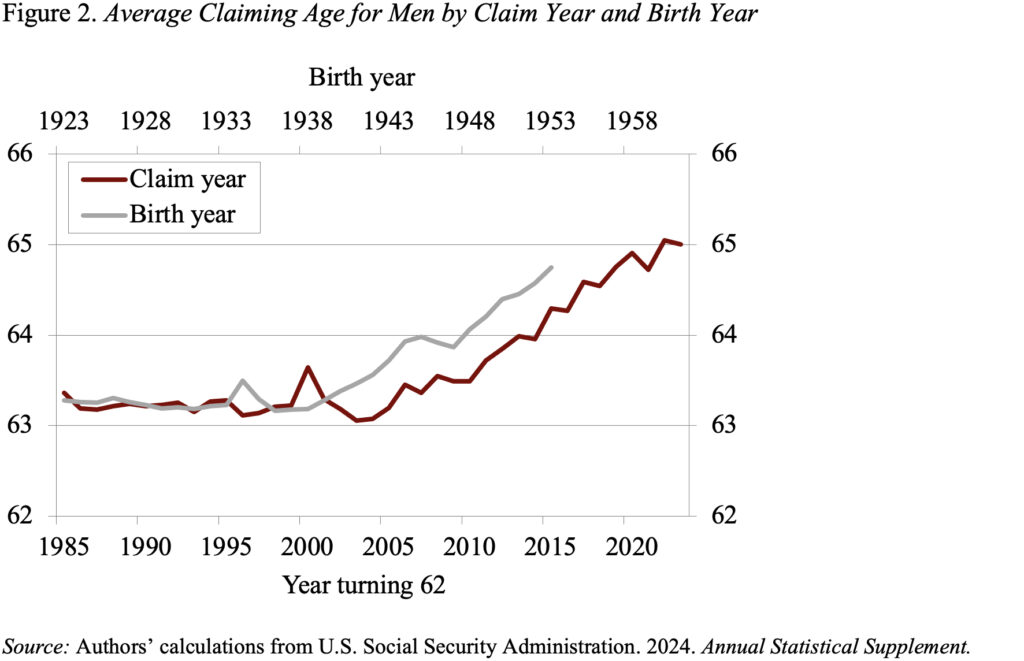

Figure 2 describes this trend in 1985-2023, the average claim age for men based on claims and birth years (the population of 62 after 2015 was not reaching 70 years by 2023). As one would expect, the increase in using birth year data is greater, but both support the argument that retirement delays are accompanied by delays in claims. However, the delay in claims (even using birth year data) is only about two years, slightly lower than the three-year increase in average retirement age.

Most importantly, the “yes” person will claim later, but the increase in claim age is slightly lower than what people expect from older job increases, regardless of the focus is what people are among people born in a given year or a given year.